By: Harlee E. Webb

He crouched down on the floor with his back against the couch, laughing as we each yelled “Can you hear me now?” into the microphones of our respective laptops. Isaac Wright, a current senior artist in the Valdosta State, Dedo Maranville Fine Arts Gallery exhibition “In Bold,” sat down with me to discuss his livelihood as a maker, as well as his work as a whole. Amid a pandemic that has shaken the world, it has become apparent that the arts are also not immune to panic and have felt the ramifications of a slowing world. Isaac discusses not only how his sleep schedule has been impacted but also his motivation, workspace, artwork, and mindset.

As we chatted via Zoom Meeting, a software that has been deemed “essential” for thousands of students and workers needing to communicate worldwide, Isaac remained cheerful, attempting to make the best out of the situation. We spoke about a wide variety of topics, but the subject of his artwork brought us back to our former days of sitting in the studio together, pondering over our ideas and looking forward to where his work is taking him.

The artist talked of his inspirations and favorite artists, including Howard Finster, who was also from the “Peach State”. Isaac describes Finster as an outsider/folk artist and mentions how he appreciates his work so much that he considers Finster a major influence in his own art. Scenes of cabins, churches, and the love of all things worn and old are seen in Isaac’s work. But that love did not come suddenly—it bloomed with time. His interest in Finster sparked as a child, when he heard the stories his father and grandfather told. “They recall a time when Finster repaired and sold bicycles and then one day just started making sculptures out of them in his backyard,” Isaac stated. “Nobody else I had seen in my childhood had that level of passion and dedication to the arts.”

Much of Isaac’s work is influenced by his childhood and the unique concept of growing up in the South. He discussed how his artwork allows him to view a lot of childhood imagery from a different perspective. “It feels therapeutic at times,” he expressed. It starts with an idea—usually a reference image—that becomes a sketch, and then he just goes for it. Isaac voiced how, for him, the process of being able to take an idea and “just doing it, going for it” is what drives him to create. While printmaking is one of Isaac’s main mediums, he discusses how ceramics has given him more spontaneity in the thought process and how working in both mediums allows for balance.

Isaac’s Reclamation, lithography, (2018) is evidence of how he can take imagery of the South and recreate it through prints. I can recall Isaac working on this specific piece; we were in the studio together, and Isaac worked at his typically slow yet precise pace. He was taking his time to reflect, thinking through all the steps. This method shows through his work, as it contains detailed shading and line work utilized to depict the complexity of an old barn. However, his carefulness shines in more ways than just through his art. On one late studio night, I accidentally dropped my plate into the acid bath. We glanced at each other before simultaneously saying “oh no.” Isaac took one for the team and suited up in goggles, an apron, and gloves that reached up to his collar bone. He stuck his whole arm in that acid bath for my plate. After digging into the caustic substance, he was able to finally retrieve the plate. I think Isaac is a Finster himself in that way; he was willing to go the extra mile for someone else’s art, and that is a passion in itself.

When Isaac isn’t risking his health for his peers in the printmaking studio, he is found in the ceramic studio, likely chatting with other students while working on his next great piece. The Twice-Fired Pitcher, Stoneware (2019) resembles this side of Isaac’s work. As a student artist, he is always striving to further develop his skills and grow. Isaac discussed how his pitcher came about through a desire to throw larger forms. In making this piece, he put two forms together to create the pitcher before firing it in the soda kiln. He talked with me about how the pitcher just didn’t come out as “toasty” as he wanted it. So, he put it in the kiln again. During our talk, he reflected on his ceramics work and how he had created so many small, rounded items that an object as big and tall as his pitcher was something he was searching for. Isaac discussed how over time his art practices have evolved and how he has found that the things he used to consider tedious, such as measuring and cleaning borders, are now things that he enjoys, faithfully practicing in his process. The Twice-Fired Pitcher, with its simplistic form and color, shows how this artist’s work is not only about showcasing a story or memory but also presenting functional work with a decorative glaze that can form its own aesthetic story.

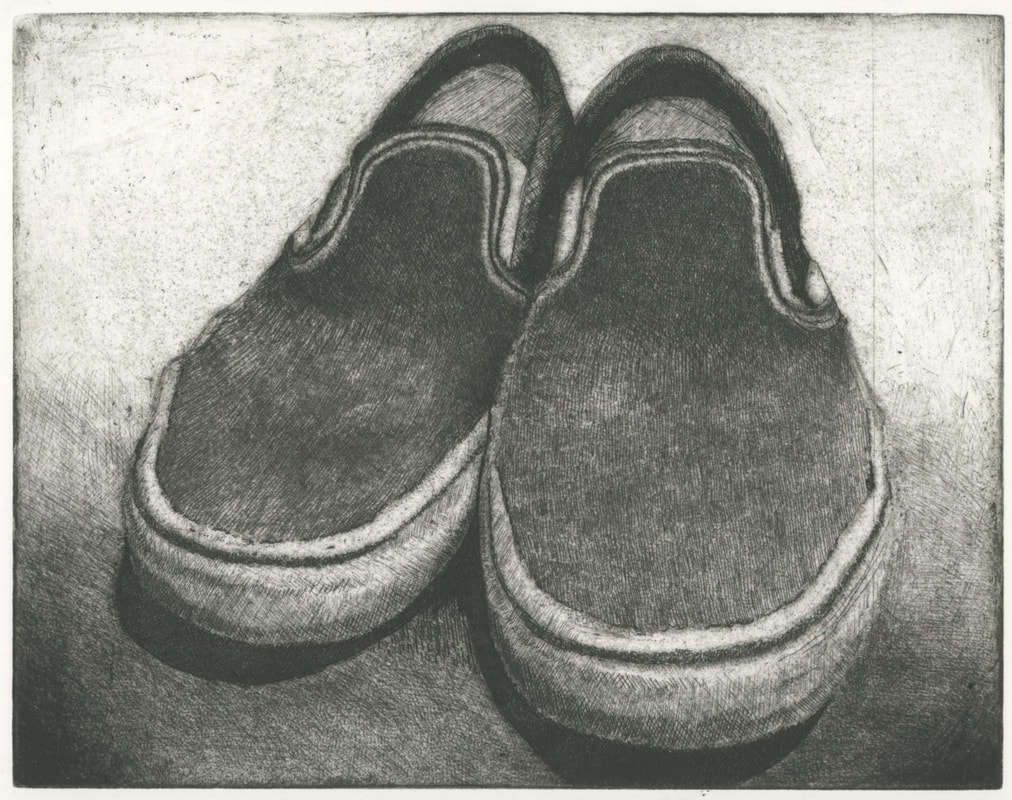

Other works featured in the show, such as Pickup, etching (2019) and Tread, etching (2019), embody the artist’s call to depict everyday imagery that might be considered mundane, to spark an appreciation for the everyday. Isaac discussed how he enjoys the nostalgia and melancholy that can come with these objects and their origin; he enjoys researching art history and tradition. To me, his appreciation of the “story” of an item reminds me of the show American Pickers and how the hosts sort through piles of refuse in hopes of finding those real historic gems. In a way, all artists are searching for gems and showcasing them in their work for the world to see. For Isaac, even a simple pair of shoes tells a story, something that Tread depicts. The piece displays a close-up view of a pair of slip-on shoes in black ink. The process of etching can be quite tedious, but Isaac makes it look seamless, as the line work and value created within the work are immaculate. He discusses how he wants his work to praise objects for their function, as well as the history they hold. Isaac’s desire to paint the everyday resembles that of both contemporary artists and art movements of the past. These artists also strived to capture moments of normalcy. In our discussion, Isaac describes Impressionism as a “pure movement” that inspires him and his art making.

While his work may grow and change over the years, Isaac knows that being an artist will always be a part of his identity. “I’m not good at anything else,” Isaac mocked, as I rolled my eyes. “This is my contribution to society.” This transition has not been easy, but for Isaac, it has opened his eyes to life as a “real artist” in the “real world,” where there is no strict schedule offered by school and deadlines are no longer the focus; work must be made from an inner motivation. But for the time being, as he continues towards the education finish line, Isaac plans on continuing his artwork. He hopes to return to the work that was abandoned in the studio in March, but this time, he aims to complete it.

Harlee is a senior in the Art Education program at Valdosta State. Upon graduation, she plans to pursue a career in K-12 public education.