by Shelby Hammack

In the second week of February of 2025, Valdosta State University’s Dedo Maranville Fine Art Gallery hosted Chico Sierra’s The Good Sun exhibition. In the beginning of the week, the visiting artist, originally from El Paso, Texas, performed live mural painting in the gallery, open for art and design students to view and converse with the artist. From start to finish, Sierra completed his 65” x 15’ painting, Slow Collisions, acrylic on canvas, prior to the opening of the exhibition. On opposing sides of the canvas, two bodiless heads, both appearing to be female, float in the vibrant pattern stained void. The two forces, facing each other, appear to collide in the near center of the canvas. In watching the development of the mural, Sierra moved about the canvas without evident rhyme or reason, which he claims is a regular practice in his artistic process.1 While being the largest in dimension, Slow Collisions is only one of many in “The Good Sun” Exhibition; though this mural captures his central area of work, the larger majority of the exhibition illuminates a central theme among his work.

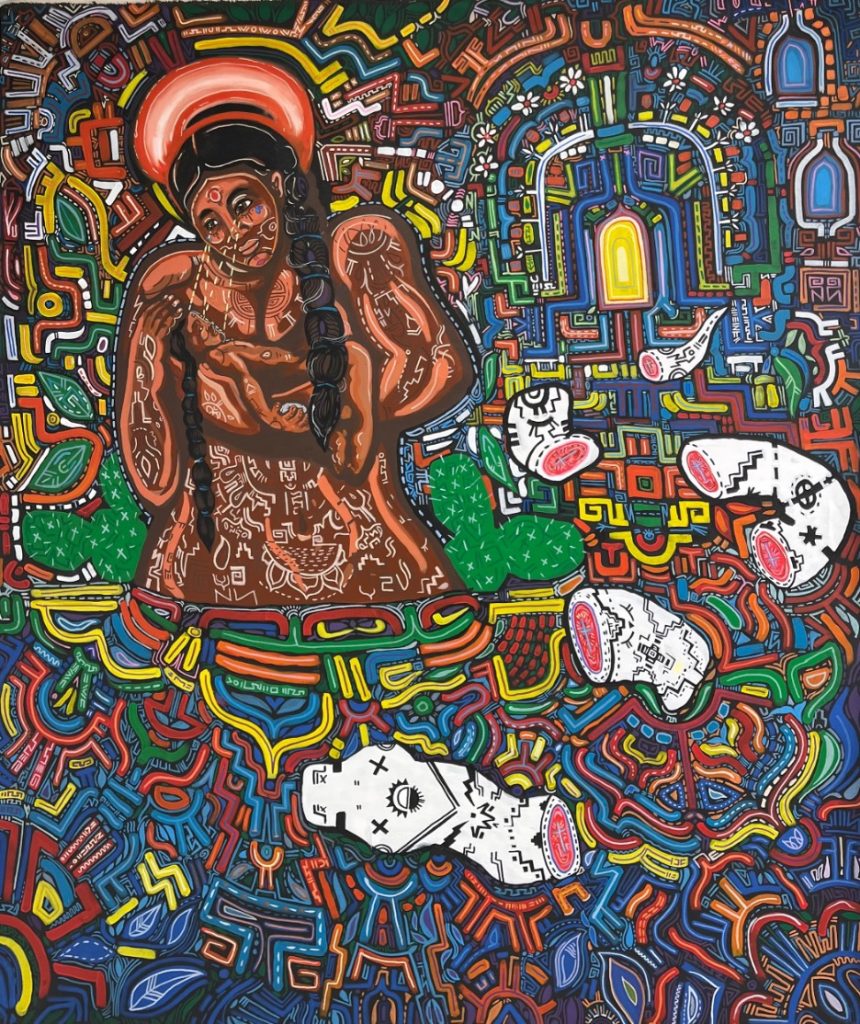

Given Sierra’s Chicano roots, the work shown in the exhibition is derived from South American spiritual and cultural iconography2, despite the artist’s opposed stance on spirituality. Some imagery includes cattle, snakes, cacti, repetitive patterns and color, and haloed figures, many appearing to be female. In reference to the artist’s background, the haloed female figure in the selection of work is speculated to be the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is a national symbol for Mexico and Mexican identity, which would directly correlate to the artist’s central theme of his Chicano upbringing and identity.

In addition to the central theme, an underlying theme of racial politics is signified through the image of a white snake, which is found in two of the selected works, Sisters of Common Threads and Revolution, and The Revolution of Inheritance, acrylic on canvas. In the latter painting, the white snake is a multi-faceted symbol for oppression and North American colonialism. Severed into five pieces, the artist exposes the meat-colored innards of the serpent, replacing the cross section of the spine with a cross. The appropriation of the Join or Die propaganda art for the French and Indian war not only alludes to the expansion of American territory, but the expansion of Catholicism – hence the cross; Sierra ultimately signifies an overcoming of oppression through disabling the snake.

Sierra’s abstracted self portrait, The Good Sun, continues the theme of identity in American political turmoil. The Good Sun, being a play on words for the phrase “the good son”, identifies the practice of assimilation: the process of immigrants adopting the common culture of the United States. Being that Sierra is an American born citizen of two Mexican parents, the title of the painting implies that the artist is acting to prove himself worthy to them, most likely through financial success. In moving to “the land of opportunity”, immigrant families tend to pressure their children to make the most of the opportunities at hand; this usually leads to substantial sources of stress and pressure to perform. With this in mind, I argue that immigrant families push for their offspring to abandon their heritage to make room for the “American Dream” they never had the chance to fulfill themselves.

Sierra breaks apart from this pattern, and reveals the journey of his healing through painting The Good Sun. The visual aspect of the painting contains a headless self portrait of Sierra, who is spreading open his chest cavity with his hands; the neutral skin tones washed with pale blue tattoos contrast against the vivid color and aztec patterns that flow from the interior of the torso to the background. In breaking open the shell of his body, Sierra reveals the South American identity that has been contained inside himself all along.

In producing and presenting his collection of work, Sierra successfully conveys identity and a sense-of-self within the exhibition, which has been thoughtfully named after his, most objectively, successful work. Sierra’s effort to uncover his truest self is evident not only in the exhibition, but in the demeanor in which it was presented. In speaking to Valdosta State University students, staff, and visitors, Chico Sierra appeared to be unapologetically himself: openly coversating, playing guitar, and holding meaningful conversations about his work and personal journey.