By: Marissa Parks

The gallery is left very open. The walls are covered in intricate, detailed black wall decals of silhouettes of fencing, birds, and even flying hand guns. These guns are just that, silhouettes of hands guns with wings attached, pinned to the wall, appearing as if they are flying around the exhibition. Laying on top of or next to these details are large paintings. In the center of the gallery are several, cushioned benches inviting the viewers to sit back, relax and enjoy the artwork, and some do. From either side of the bench is a fair amount of distance from the pieces on the wall, allowing the audience to appreciate the large works in its entirety. This accessibility to comfort in the galley encourages viewers to stick around. The Dedo Maranville Fine Arts Gallery in Valdosta, Georgia presents “Bearing Witness: Installations by Margi Weir.” Weir travels from Detroit, Michigan to exhibit her controversial work. It’s clear that Weir has an opinion and is very direct with the delivery of expressing her views.

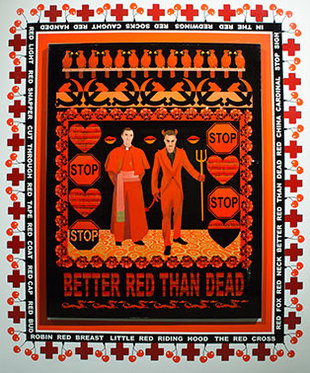

The piece Blue is Not a Neutral stands out specifically, not only because of its vibrant blue color, for the content of the piece. She repeats the use of silhouettes from the decals on the wall into this painting, but in this case, it is the silhouettes of four officers standing side by side wielding batons. Their stance and body language suggest they are prepared for attack, not defense. They do not have their arms up shielding themselves in defense, but by their sides as if they’re unthreatened. The word “Police” is clearly displayed across the figure’s chest in white font. The line of officers stands in front of a gradient, blue brick wall. Hanging above the officers is a blue, first place ribbon. Weir is clearly trying to convey and imply that law enforcement will never see themselves as equals to civilians, in fact, that they act as if they are superior and use their authority against common folk. She makes another bold statement with her painting titled Gold Standard. In the piece are icons of gold stars, the Oscar awards and the iconic, golden McDonald’s arches. Weir implies that society sets the gold standard and uses it as a way to brainwash people into thinking what is “good” or the “gold standard.” In her piece Better Red Than Dead she compares a devil to a priest using a red color palette. There are red stop signs, hearts and lips surrounding the two figures. These symbols suggest that the church is just as bad as the devil and hinting at sexual misconduct and abuse within the church.

All of Weir’s pieces are powerful and convey a strong message. She’s not afraid to stand up for what she believes in and is strong in sharing her views on what is right and what is wrong, regardless of the stir it may cause. She confidently expresses her feelings while visually communicating topics that are normally hard to talk about.