The use of spatial statistics to study processes that affect dispersion is the unifying theme in the Anderson lab. Because the lab is analytically focused, we tend to work on a wide array of projects and study systems. While we are not focused on a particular organism, recent empirical work in the Anderson Lab at VSU has tended towards structurally dependent plants (epiphytes and vines) and burrow ecology (of gopher tortoises and armadillos), as these systems are regionally relevant and well suited for spatial analysis.

CURRENT LAB PROJECTS

Direct, indirect, and diffuse interactions between structurally dependent plants

The spatial ecology of Spanish moss

Epiphytes are structurally dependent plants that live on the surface other plants (usually trees). Their distribution in a forest can be complicated, making it difficult to make simple statistical inferences about associations between host tress and epiphytes.

Our lab has been surveying the spatial distribution of an ecologically and culturally important epiphyte species, Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides), in different forest communities. Our initial work on this system involved characterizing and modeling the spatial distribution of Spanish moss in early successional forest systems (i.e., pine stands and mixed pine-hardwood secondary forest), and our results indicate that the probability of Spanish moss occurrence is higher in areas with larger hardwood trees that abut source populations in old-growth hardwood forest. More generally, our results suggest that landscape level patterns and disturbances that affect hardwood encroachment in upland areas.

A hard edge (formed by a road) between hardwood forest and burn-managed pine forest. Research in the Anderson Lab suggests that, in pine forest, most Spanish moss occurs near stand edges that abut hardwood forest and that the most important predictor of Spanish moss occurrence in pine forest is the distance to such source populations.

Interactions between structurally dependent plant species

Our work on Spanish moss has raised interesting questions as to how vines and lianas may modulate the presence and abundance of Spanish moss on a host tree and, in the process of exploring this question, we have become increasingly interested in the interactions between the vine/liana species themselves. In the fall of 2017 and spring of 2018 we surveyed live oak (Quercus virginiana) trees in the mixed-pine hardwood forest at Lake Louise. Vine richness ranged from one to six with a mode of four, and preliminary modeling indicated that certain species (namely the liana Vitis rotundifolia) may be acting as an important secondary foundation species (that enhances the richness and thickness of other vines on a tree).

Wild grape (which can be seen hanging in the center frame) is a liana (a woody vine). Our research demonstrates that when wild grape is present on live oak, there tends to be more species of other vines and the vines grow thicker around the tree.

More recently, we have set up some preliminary experiments: 1) to compare performance of Spanish moss on different substrates (including multi-species vine tangles and lianas) and 2) to compare the colonizability of pine trees with and without vines (following a prescribed burn). The latter has us increasingly interested in the assembly of vine species on trees, as our observations suggest that Smilax tamnoides and S. glauca are usually the first species to colonize a tree [followed by Vitis rotundifolia and Gelsemium sempervirens].

In summer 2019 we set up some preliminary experiments to examine how well Spanish moss performs on different substrates, including multispecies vine tangles and a liana (Vitis rotundifolia).

Spatial ecology and genetics of brumating and burrowing animals

Some species dig or use holes in the ground as refuges and their daily and seasonal movement patterns may be dependent on these locations. Early work by the Dr. Anderson looked at the effect of overwintering hibernacula on patterns of movement and mating between den populations of the timber rattlesnake in St. Louis County, Missouri. As snake dens are exceedingly difficult to locate, more recent efforts have focused on examining the spatial distribution of gopher tortoiese and armadillo burrows, as such features can be easily identified, mapped, and represented as a point pattern; such burrows also turn out to be very ecologically important, as they are often used by other commensal species. The lab is now working on a large number of projects involving the use of point pattern analysis to test hypotheses about processes affecting the distribution and co-distribution of such burrows.

Armadillos and gopher tortoises are both prolific excavators of underground refuges, but they will also use burrows dug by the other species. Shown is a gopher tortoise burrow that has been co-opted by a nine-banded armadillo. The armadillo has packed pine straw in the burrow to make it a better armadillo nest.

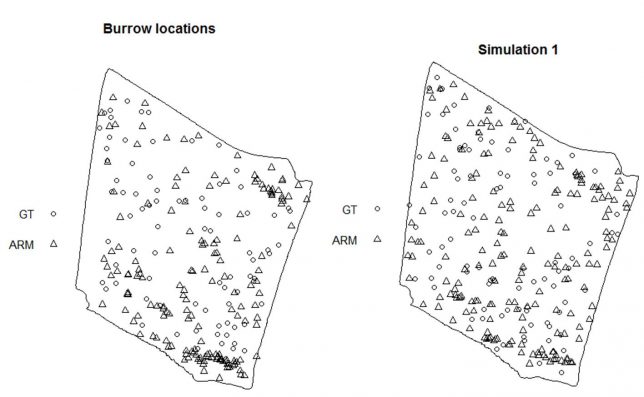

Armadillos have rapidly expanded their range in North America and now co-occur in many areas with gopher tortoises. Previous studies have shown that armadillos eat gopher tortoise eggs and evidence of antagonistic interactions between the two species, but it is unclear whether one species affects where the other burrows. Our lab is using a combination of point process modeling with second-order point pattern analysis to determine if the point processes are independent. Here we have fit an inhomogeneous multitype Poisson point process model so that we can account for covariates in Monte Carlo simulations and correct for inhomogeneity when using bivariate summary functions.

Armadillo research

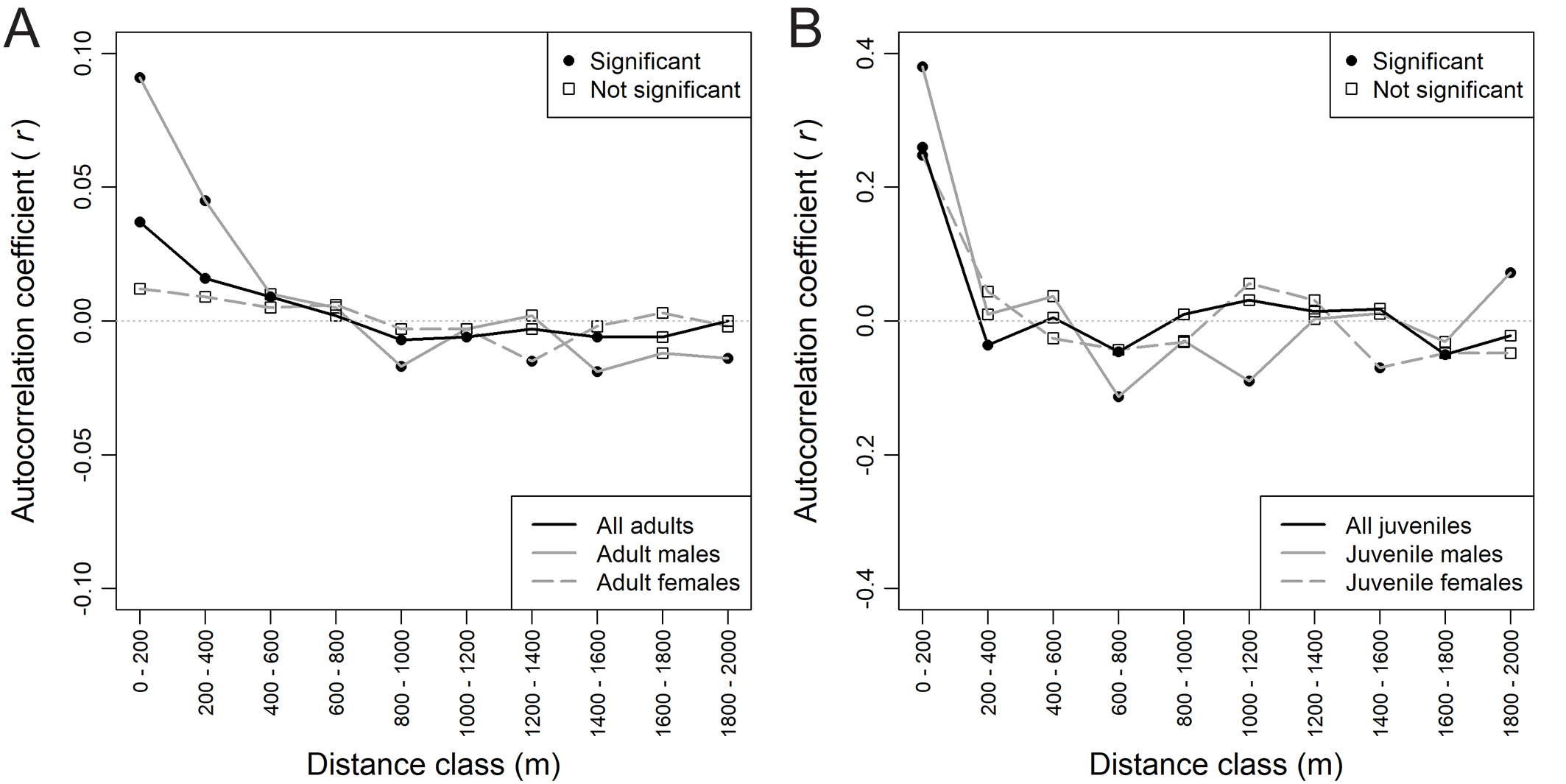

The Anderson Lab has also been collaborating (with W.J. Loughry and C. McDonough) on a variety of other projects involving the nine-banded armadillo (Daspypus novemcinctus), including: 1) the spatial pattern of leprosy prevalence in an armadillo population, and 2) spatial genetic structure in different sex/age classes of armadillos. The latter project has yielded evidence of male-biased relatedness structure in the Yazoo, Mississippi population, which is unusual for mammals.